Photo Credit: FC Campus Communications

In the midst of the growing Black Lives Matter movement, changes are starting to be seen as a growing movement of activists and civic leaders works to dismantle systemic racism across the country. Systemic racism, also known as institutionalized racism, is the practice of normalizing racism within many parts of civic life, including criminal justice, health care, employment, politics and even education.

A new law in California is attempting to challenge that.

Gov. Gavin Newsom approved Assembly Bill 1460 on Aug. 17, requiring California State University students graduating in the 2024-25 academic year to have completed a 3-unit class within Native American, African American, Asian American or Latina/o studies.

CSU is the largest public university system in the country, and AB 1460 makes California the first state to require ethnic studies as a graduation requirement in public universities. That means all 430,000 California colleges will increase course offerings in these fields to accommodate the new requirement. According to the CSU chancellor’s office, this is also the first significant change to the Cal State Universiy’s GE requirements in 40 years.

Edward Robinson, African American studies lecturer at Cal State University, Fullerton, explains that he can see universities in other states making this a requirement as well. He says it would look bad to the public to not follow in California’s progressive footsteps. Robinson points out that students of color will see this change and begin to push to have these changes made within their university campuses.

Ethnic studies is the interdisciplinary study of race and ethnicity, and includes sexuality and gender, along with other parts of society.

For example, in African American studies, students are taught more in-depth about slavery. Rather than in traditional education where students are taught briefly about slavery and how Abraham Linclon abolished it, in African American studies, people are taught the roots of African civilization and the lost arts that many people do not know about. Lessons about the tribes and how they traded is an important factor in history, but is rarely taught outside of these classes. Students are then taught about the laws that were made during the founding of the U.S. that took all rights away from Africans and made them slaves. This is just a very small portion of what people need to be taught and may not know about unless taking African American studies.

Amber Gonzalez, associate professor and chair of ethnic studies at Fullerton College, says the change is critical for students of color.

“This really validates their experiences. Giving them a language to be able to understand their experiences is also very empowering and really necessary because oftentimes students have absolutely no reflection of themselves in their course work their entire lives. So absolutely one course in their entire college career is a small gesture on part of the CSU to say ‘your stories matter.’”

Controversy over ethnic studies

This bill has caused a debate between ethnic studies supporters and CSU. In March 2020, Cal State Chancellor Timothy P. White’s office approved a separate ethnic studies and social justice requirement that would have included Jewish, LGBTQ and women’s studies, giving students more options from this broad spectrum of classes to fulfill the graduation requirement. That bill could have ultimately allowed them to avoid ethnic studies all together.

Newsom had a choice to then either allow White to go ahead with this proposal, which was basically a middle ground between ethnic studies allies and those opposed to the bill, or approve AB 1460, which overrides the requirement passed by CSU.

According to Gonzalez, many institutions have been against including a dedicated ethnic studies requirement because the courses challenge the status quo and shed light onto hidden histories.

“The CSU chancellor created the social justice and ethnic studies requirement as a way to kill AB 1460 and as a way to detract from the original intentions of what ethnic studies is, because ethnic studies does look at gender, sexuality and religion,” says Gonzalez. This means that ethnic studies already goes into the same detail that individual social justice classes would.

AB 1460 was written by Assemblymember Shirley Weber, Africana Studies professor at San Diego State. She wrote this bill on behalf of the California Faculty Association and with support from the legislative ethnic caucuses. In an interview with KUSI News Weber explains that this bill is something she has been working towards for 50 years, dating back to the student-led strikes that gave students their first ethnic studies courses.

Chancellor White and his office disapproved of this bill because they did not believe the government should have power over the CSU’s curriculum. They also argued they already have required courses that would fulfill a broader ethnic studies requirement like anthropology or women’s studies.But proponents of Weber’s bill ultimately argued that those courses don’t teach the disproportionate, lesser-known histories of ethnic minorities.

Ethnic studies advocates oppose casting such a wide net for a “social justice” requirement. They say it detracts from the importance of studying these specific ethnic groups and also devalues the importance of these other fields. The CSU Ethnic Studies Task Force in a report in 2016 discussed how it is harmful for institutions to group these courses together. “Some were concerned when their institutions treated one form of diversity as interchangeable with any other,” the report states.

CSU’s proposal would have cost an estimated $3 million to $4 million a year, according to the chancellor’s office, while AB 1460 would cost upwards of $16.5 million a year.

Hazel Kelly, public affairs manager of the CSU chancellor’s office, explained, “The estimates are based on potential increases to the number of faculty needed to teach additional courses in ethnic studies and to revise transfer pathways with the community colleges so that CSU can comply with previous mandates related to the associate degree for transfer.”

Cheryl Marshall, chancellor of the North Orange County Community College District, explains that Fullerton College will be making adjustments as well for the students to have ethnic studies options.

“Adding a course to the department will cost, on average, $3,600 per section. However, it is anticipated that students who chose to take an Ethnic Studies course to meet the new requirement may not have to take a course in another discipline. As such, we may not see a significant increase in costs due to a realignment of resources across the campus.”

Roadblocks to changing high school curriculum

At the time AB 1460 was passed, a similar bill was gaining support from the legislature. Assembly Bill 331 would have required high school students to take a one-semester ethnic studies class to graduate. On Sept. 30, after both the state senate and assembly passed the bill, Newsom declined to sign it, saying the bill needed more revision.

Gonzalez explained this has been something advocates have been wanting since the late 1960s and early 1970s. AB 2772 in 2018 was another version of this bill, which was also created by Assemblymember Jose Media, but was struck down as well.

“Teaching everyone American history from the lense of Native American, African American, Lantia/o or Asian Americans would give them the language and knowledge needed to make a change in U.S. society,” says Gonzalez. “Those opposed to these classes would prefer to keep their hierarchies that we see today in different forms of privilege and their way of life.”

Robinson explained he isn’t too worried about AB 331 not being passed. “There is always a white backlash to any perceived advancement of people of color in the United States,” says Robinson. “Voting matters and minorities in California have built a strong voice since the 1990s and those who struck down the requirement will face consequences.”

Taking an ethnic studies class in high school prepares students sooner on how to be empathetic towards others in their jobs and daily lives. Not every student goes to a community college or CSU. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor, 66.2% of high school graduates in 2019 were enrolled into a college or university. The other 33.8% go straight into the workforce or go to a trade school, thus leaving this percentage out of the ethnic studies education. Expanding ethnic studies to high school will help young minds be able to start being more inclusive at a younger age.

The roots of the struggle

Photo Credit: FC Campus Communications

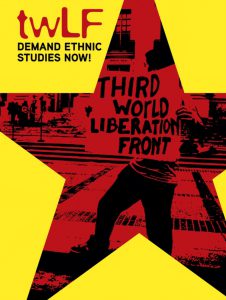

In 1968, the fight for ethnic studies started at San Francisco State College. This was the longest student-led strike in U.S. history, started by the first-ever Black Student Union and the Third World Liberation Front, from November 1968 to March 1969. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X had been assassinated, the Vietnam War was ripping families apart and drafting people of color at higher rates than their white counterparts, and the Black Panther Party was demanding systemic change.

Acceptance rates for minorities were low at San Francisco State College at the time. Black students joined together and formed the first Black Student Union, demanding the administration accept a higher rate of Black students. They asked for 400 Black students to be admitted in fall 1969 and the administration acquiesced. But, when the Latinx and Asian students heard about this, they wanted to be better represented as well. They asked for the same thing, but were told to ask BSU to share a portion of the 400 spots. This caused BSU students to be angry, so the Black, Asian and Latinx student groups joined together in solidarity to form the Third World Liberation Front. They wanted to challenge administration for better representation in greater numbers. They had 12 demands, including that the university set up a school of ethnic studies, increase admissions of people of color, and rehire an English Professor and member of the Black Panther Party who had been fired for speaking out against the Vietnam War in his class.

Demonstrations led to unrest, and the police were called the first day of the student strike. They started macing and beating students with batons, which caused a full war on campus. Students started throwing rocks and setting off cherry bombs under staircases and in toilets. When word got out about this, faculty and local Black activists joined in the protests to help the students. According to NPR’s Code Switch podcast episode, “The Long, Bloody Strike for Ethnic Studies,” on day 79 of the protest, 483 students were arrested and several ended up serving anywhere between 30 days to beyond one year. Some activists tell how they turned 19 in jail or spent graduation in their cell.

In March of 1969, a negotiation came together. After five months of protesting, San Francisco State agreed to create the first College of Ethnic Studies and the school promised to accept all students of color who applied in fall 1969. But George Murry, the English professor and minister of education for the Black Panther Party, was not rehired. Many saw this as a settlement rather than a win for people of color.

Since then, it has been a struggle to get the rest of California on board with more widespread policies that create inclusive courses and campus environments. Newsom’s approval of this bill shows how important that strike was and how the struggle has remained active over the last 50 years.

Former student activist, Jose Castaneda III, explains in 2014 he fought and won ethnic studies as a graduation requirement for incoming first years and transfers at CSULA.

He says, “I am glad the CSU implemented an ethnic studies requirement because it means Black, Indigenous and young students of color will finally have our histories taught just as any U.S. history course is required because ethnic studies is U.S. history, only it goes a step further to empower BIPOC students and families to become more civically engaged.”

There have been movements since then for ethnic studies to be funded in universities and colleges. In 1999, Third World Liberation Front students led a hunger strike and protest at UC Berkeley after an ethnic studies budget cut. On the sixth day of the protest, 81 students were arrested. This strike resulted in the creation of the Multicultural Community Center and more faculty being hired for the ethnic studies department. In 2017, students at USC started a petition for more Black history courses at the university. Fullerton College is now offering an Africana Studies AA degree and plans to offer American Indian and Indigenous and Asian Pacific Islander AA degrees by fall of 2021, according to Marshall. And there has been the ongoing fight for ethnic studies in high school, despite recent hurdles.

But the fight for ethnic studies is not over. “We know things don’t change in history because those in the ruling and oppressive classes grant it to the oppressed out of their own goodwill,” says Gonzalez. “It takes the oppressed people to push the envelope to make these changes happen, to create a better world for all of us.”