Poetry has the potential to bring together what some say to be a divided nation. It speaks about personal experiences and how to cope with them. For many poets, poetry is also a vessel they can use to press concerns they have regarding life around them and how they believe these can be fixed.

Amanda Gorman, a Los Angeles youth poet laureate and, at 22, the youngest inaugural poet in U.S. history, conveys the power of poetry and how it can be political.

“Poetry has never been the language of barriers, it’s always been the language of bridges. It’s that connection-making that makes poetry, yes, powerful, but also makes it political,” Gorman mentions during a TED Talk.

Poets have the ability to rewrite the nation, with the words and fearlessness they speak, taking on certain issues in society. Gorman writes in her poem In This Place, “the protestant, the Muslim, the Jew, the native, the immigrant, the Black, the Brown, the blind, the brave, the undocumented and undeterred, the woman, the man, the nonbinary, the White, the trans, the ally to all of the above,” portraying the hopefulness in united integrity.

Political poetry is defined by poets as a type of writing style that is related to activism, protest, and social concern. It also comments on social, political or current events.

Stacy Russo, an Orange Country poet, explains that the types of poetry that might be considered political are, “Someone speaking about racism, someone speaking about feminism. That content is then easy to see as political poetry.”

How a poet’s writing evolves with time and history, must also be taken into consideration. A poet can take us on a journey through time, to help us understand how our world once was, to where it can be.

How a poet’s writing evolves with time and history, must also be taken into consideration. A poet can take us on a journey through time, to help us understand how our world once was, to where it can be.

Hmm Chicanx Femme, a Santa Ana poet, explains the transitions of poetry according to each era and the change it endured through each decade within American and general poetry.

“Poetry was very confined in Iambic pentameter, in the 18th century. Then you get into poetry evolving with the American Civil War, and you start to see the free verse poetry come to life at the end of the 19th century. Then you see the beginning of World War I and World War II, and how poets interact with the changing of times,” she states.

Chicanx Femme gives an example of T.S. Elliot, whose poetry style evolved as times changed, writing with responses to the “Lost Generation” of World War I.

Issues disrupting the unity within the United States is something that many poets feel the urge to bring to light, while others may turn away from.

“You have so many Latinx, Black, Asian poets and it’s something that you’re seeing more often because our people are basically saying ‘hey, we are not being represented,’” says Chicanx Femme, as she describes the desire poets have in bringing representation and expression to heritage in a learning society.

Chicanx Femme writes poetry on envisioning a new world and getting rid of mass incarceration. “I also touch upon the immigrant experience, about how people do start over all the time… In the immigrant rights movement, you really see how the narrative of immigration has now started to embrace concepts of capitulation because detention centers are an extension of mass incarceration.”

Chicanx Femme’s poetry is an example of how poets perceive injustices that occur across the globe. Poets have the ability to push for change and make people listen—building those bridges and connections with their audiences. Just by reading a poem one is able to learn about someone else, and what they are going through in any point in time.

“Poets and writers in general are able to perceive the world from a bird’s-eye view in a sense, they are able to see everything to deconstruct it,” Chicanx Femme says.

Political poetry holds an important place for writers—being able to have a voice and use it as a way to help others. They are able to listen and observe the world around them to proclaim those stories.

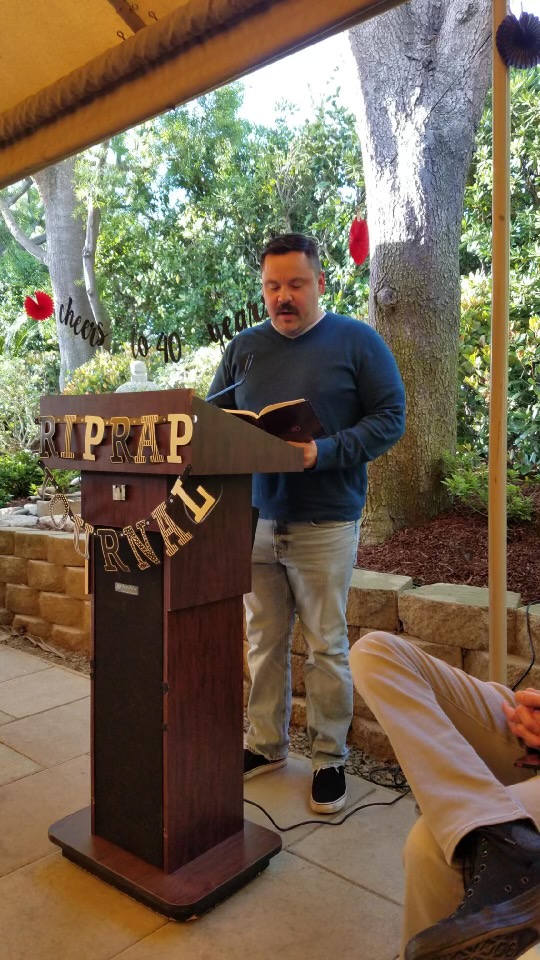

Gustavo Hernandez, a poet and author who writes about immigration as well as his experiences within his community of Orange County, says, “My poetry is very political because it talks about our place as immigrants, me specifically as someone who is Mexican, an immigrant, and I think that in writing my poems I am giving myself a voice. One of my biggest hopes with poetry is that I inspire others who may feel like their voices are not important.”

Hernandez supports Gorman’s notions of poetry and how it can build bridges. He uses an example of Joy Harjo, a poet laureate and the first Native American to hold that honor. Harjo provides that bridge to readers by establishing a connection, writing about the joy and struggles of everyday life of Native Americans.

“Here I am someone, who is Mexican; Joy Harjo is Native American. There are things that I see in her work that absolutely resonate with me. So, she’s here and built a bridge not only for me to see her experiences, but at the same time she also built a bridge for my voice,” Hernandez says. Recognizing the styles that Harjo exhibits is something Hernandez takes into account when he writes, and how he speaks about the life of a migrant.

— | Think of a stem growing north and a bloom spreading | is a line from one of Hernandez’s books. It is how he portrays immigration and his story of how his family came from Mexico into the United States—growing in one place; blooming in another.

Some poets embrace their heritage as they write about their experiences. They write with the notion of not knowing whose perspective they might change for the better.

“Some poets are sharing so much of the trauma they carry within their identity,” says Hatefas Yop, a poet in Santa Ana.

Yop, who at first did not consider her poetry to be political, began to acknowledge and embrace her poetry as such when she began covering topics related to intergenerational trauma in the United States. Her work also speaks on violence against children and women, as well as injustices in healthcare and school systems in other countries. Poetry is how she humanizes those narratives.

“In some ways poetry definitely breaks barriers and bridges communities together, like for myself, I identify as an Asian American; as a Muslim growing up in a very Latinx-concentrated part of Orange County. There’s so many layers to it,” says Yop. “However, in the different, very genuine open mic and poetry spaces that I’ve had the honor to perform at, I’ve met so many diverse folks where friendships were built.”

So many people who may be ethnically different can share one thing in common: the humanity that poetry brings out in them.

Russo takes into consideration that we can learn from all poets, “especially if we read poetry by people who may be different from us, and that can be different in a lot of ways: racially; a different economic class; maybe they live in an entirely different area of the world. Whatever it is that makes them seem different, we are going to find connections in their poetry.”

In the words by the Roman playwright Terence (Publius Terentius Afer), poet Maya Angelou recites in her life lesson speech, “Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto.’ Which is Latin for “I am a human being. Nothing human can be alien to me.”

We are all human beings existing in one world. Figures with the same erythrocytes inhabited by each layer of skin cells, regardless of color, gender or status. In the end, it comes down to the important changes poets crave: equality, equity and empathy.

Hernandez takes a moment to say where the power of poetry will take society.

“We are in a moment right now where poetry is showing its presence, its importance again, and I think that through these growing pains that this country is experiencing is a sign that a lot of us are growing really tired of being marginalized. And I think that poetry is going to be the song that accompanies the battle.”