Getting up in full drag with a fiery red wig and pink dress on a Saturday, Phillip Hurt is the only drag activist out on the streets of El Monte. In addition to looking pretty, Hurt fully embodies the spirit of queer resistance. When it came time to face the intolerance in the city of El Monte that was exacerbated by the presence of a new pastor, Hurt recounts, “The protest I did was not just with him, but anyone in the community who didn’t want to support womxn, queer, Black and trans people”.

Tensions between the El Monte community and an anti-LGBTQ+ church were sparked when a viral TikTok created by Hurt, an El Monte local drag artist and activist, spread across multiple social platforms. This content shed light on the multiple conservative preachings of Bruce Mejia, head pastor at the California Chapter of First Works Baptist Church (FWBC). While the church seemingly sprang out of nowhere, the FWBC previously resided in Maywood.

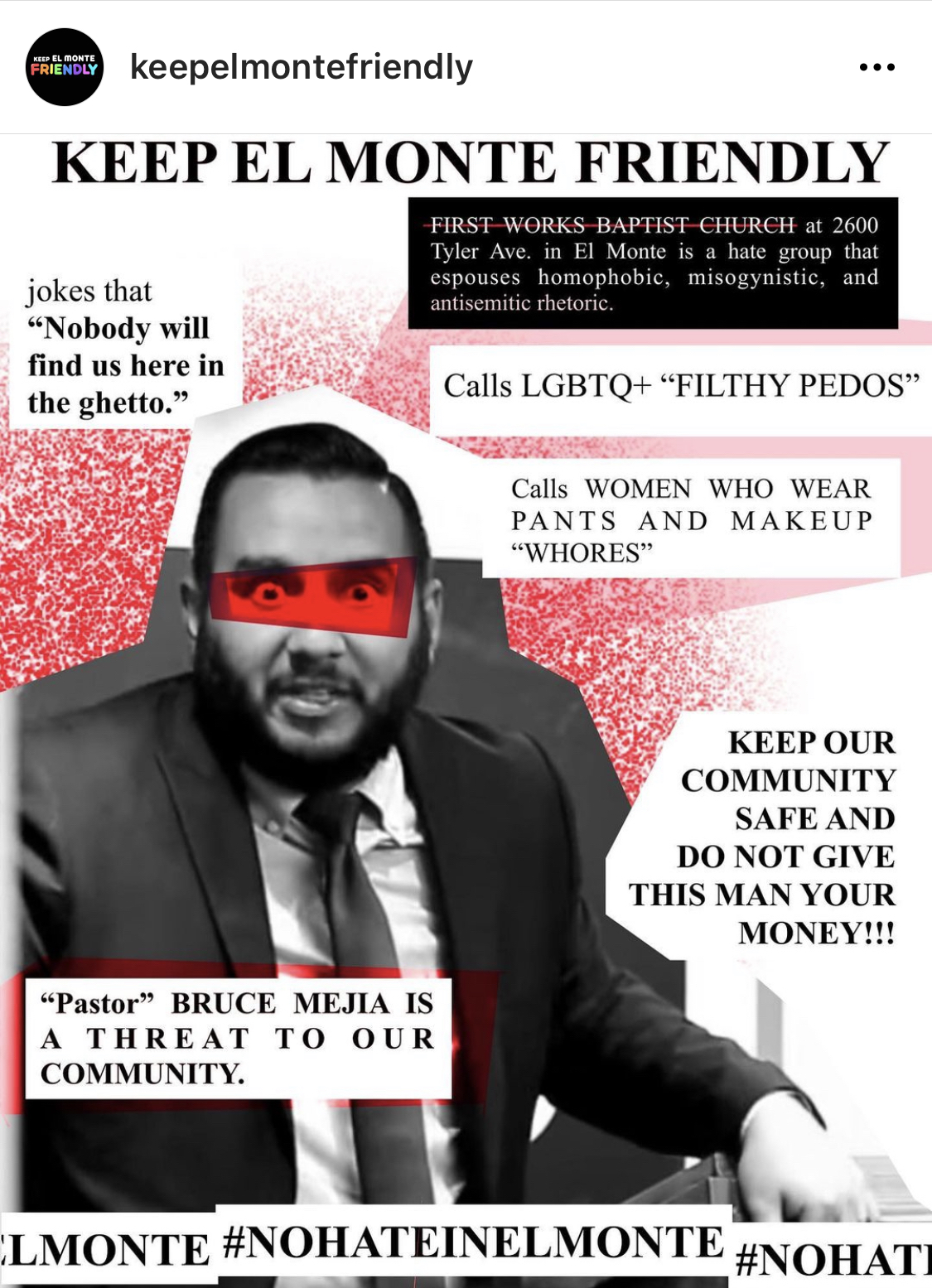

Activists like Hurt have kept their eye on the FWBC after their move into El Monte, especially after their investigative findings on Mejia: previous preachings encouraging the death of LGBTQ+ people; Mejia’s personal connection to the head preacher of FWBC; condemning womxn who work; speaking against the Black Lives Matter Movement. In 2020, the FWBC was listed as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center for spewing hate speech against the LGBTQ+ community. Through his sermons, Mejia has developed a reputation for his hate speech against LGBTQ+ communities and trans and gender-nonconforming folks.

But his ideologies are not his alone. Mejia was once under the mentorship of Pastor Steven Anderson, who has previously praised the occurrence of the 2016 massacre in Orlando, in which many LGBTQ+ folks were killed at the Pulse Nightclub.

According to Hurt, Mejia carried on similar rhetoric by referring to the more commonly used LGBTQ+ acronym as, “Let God Burn Them Quickly,” and constantly referring to queer folks as sodomites and pedophiles. Yet, this rhetoric did not stop activists like Hurt from coming to the forefront.

Hurt’s exposure to the FWBC and eventual activism against their messages came as they were scrolling through Facebook pages related to El Monte. As an activist, it was important that they stay as up to date with their hometown as much as possible because of their “Natural Chola instincts and punk aggression.” Having been born and raised in El Monte, Hurt’s passion for keeping the city inclusive is not surprising. Years prior to their activism, Hurt was involved in the prior church that sat where the FWBC once did, mainly because of their mother who volunteered there.

While Hurt no longer considers themselves to be religious, they still recount how the previous church was dedicated to being as supportive for anyone who walked through their doors as possible. When the FWBC overtook the location on the corner of Tyler Ave and Elliott, Hurt reflects, “What breaks my heart is that the church before… was like a little haven for previous addicts… the homeless y todo, and they even had AA meetings at one point. And to know that church disappeared and this one took over really broke my heart, especially with the hate this man is bringing.”

As a queer femme, Hurt was also concerned about Mejia’s messages about womxn and other femmes involved with the Black Lives Matter and trans rights movements. “When I started looking at his videos, [he’s] not only attacking the gays… he also targets women. He’s known to have said that if women work, women are whores and women are basically weak…”, Hurt says, recalling watching Mejia’s sermons.

For Hurt and many other LGBTQ+, womxn, Black and trans rights activists, it was imperative to keep the city of El Monte safe and all other cities that may house another FWBC church. To achieve this, Hurt came together with other activists and members of the community to establish the “Keep El Monte Friendly” collaborative. These El Monte youth were the main force behind the protests against the church.

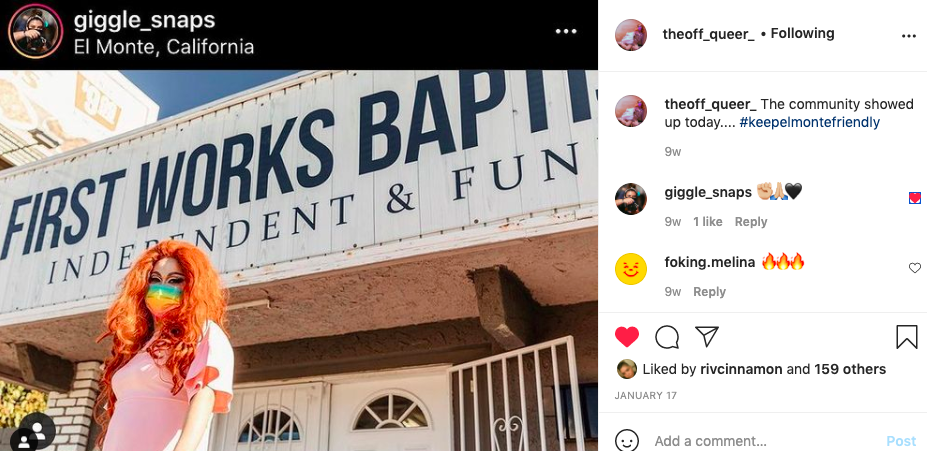

In response, Hurt attended the caravan protest that took place between Tyler Street and Elliott Ave. on Jan. 17, organized by the Keep El Monte Friendly collective. Hurt showed up adorned in full drag— a statement that made it clear that when it came to El Monte, hate of any kind was not permitted especially, “Not my fags and my femmes.”

For the sake of avoiding the spread of COVID-19 and the protection of both parties, Hurt made it clear the protestors made an effort not to step on the sidewalk attached to the church per the El Monte police’s guidelines. Though the church’s ideologies were opposite Hurt’s and the other protesters, respect for boundaries were kept, especially for children and womxn in the church.

Hurt’s activism in drag is rooted in deep cultural beliefs of respect because, “Growing up in the Chola culture, numero uno is respect—if you don’t respect me, I get aggressive, and the way I channel aggression is: ‘we gotta confront.’” During this confrontation, El Monte police remained primarily neutral, even when, according to Hurt, an underage female protestor had been touched by a male member of the FWBC, and when Mejia inquired to the police on whether they would remove Hurt and the other activists.

“But there was an incident,” Hurt says, “…where [another] protestor… they were actually right next to Bruce Mejia… and Bruce actually shoved him, at the same time making [the protestor] cross the line.” In an attempt to continue the protest with minimal contact and violence, Hurt warned the police that if anyone protesting against the church were to be taken in handcuffs or harassed by any members of the FWBC, they would be recorded by activists filming the event.

Regarding the actual members of the FWBC church present during the demonstration, Hurt points out that many were not from the city of El Monte or California at all. Upon investigation and seeing the members themselves, Hurt recalls that nearly all of the blue-eyed, blonde church sympathizers were from out of state. When the protest was over, many members of the church flocked to Hurt’s social media to make homophobic comments and even went so far as to directly message their sister for defending the activist and telling Hurt to die by suicide, including Bruce Mejia himself.

Though these comments from the counter collective created by the church, called “Keep El Monte Safe” on social media, did not shake Hurt and the many members of the Keep El Monte Friendly collective, a bombing that took place on Jan. 23, a week after the protest, stirred up suspicion of who was to blame.

According to the El Monte Police Department, officers arrived at the scene around 4:30 a.m., to find the windows of the church blown out due to an explosion from the interior of the building. Upon investigating the bombing, the FBI has determined that the device that caused the explosion was homemade, and as of March 31, the agency has issued a $25,000 reward for information on possible subjects: a male and female whose photos have been released to the public.

Prior to the attack, the collaborative had planned another protest to take place the following Sunday, on Jan. 24. After the reports were made, the Keep El Monte Safe collective posted about the incident, which Hurt clarifies, “The Church released a statement saying that the Church was bombed by protestors…,” further creating a narrative that the protestors were to blame. However, the Keep El Monte Safe collective made it clear in their Instagram post regarding the event that, “We do not condone hate crimes and are not responsible for the IED [improvised explosive device] that was set off at First Works Baptist Church. The members of our organization have never had access to the inside of the building nor do we have any interest whatsoever in defacing property or harming the individuals of the group.”

Hurt adds, “We were against what they were for, but would never hurt them—that’s not what we do.”

While the FWBC claims that the bombing was a hate crime, authorities have yet to frame it as such. Hurt believes it is questionable to frame the protestors as main suspects considering that glass from the explosion shot outwards and the graffiti tagged on the church was not similar to the tagging of El Monte locals.

Though the church itself has appeared to have moved on to their next location—Mejia followed the bombing with a preaching the day after dedicated to the persecution of the “sodomites” and “terrorists” who he believed bombed FWBC—, Hurt and other members of El Monte have remembered the rhetoric the church left behind. For Hurt and others, “The bottom line was that the danger was there, no matter when it was, no matter how it was – that danger was there, the danger presented itself, [and] they have radical ideas about what religion is to them.”