Sports teams moving from city to city is not uncommon. In 1949 the NBA introduced the Tri-Cities Blackhawks. The team played for a couple of years before relocating to Milwaukee. They moved a few more times before staying in Atlanta, where the team currently resides. While this team has called multiple cities “home” and had generations of coaches and players come and go, in over 70 years the one thing to stay the same has been their mascot. They are still Hawks.

Currently in North America, there are a total of 151 Major League sports franchises, most of which have mascots. They are typically good luck charms for the teams, help get a lot of fans pumped up for their games and create personal connections with fans. Every team faces obstacles to keep their mascot relevant, whether it is, like Fullerton College’s Buzzy, updating their look, completely altering their image to more closely align with social change, or simply moving to a new city.

The Atlanta Hawks originally derived from three cities once native land to the Kickapoo, Sauk and Fox Indians. According to North Illinois University, these tribes were participants of the Black Hawk War led by the leader of Sac and Fox Indians, Black Hawk. These cities dedicated their mascot as a tribute to this leader.

The connection between a mascot and a team is not always easily drawn, and some teams’ mascots can become an almost comically fun representation. When one thinks of jazz, Utah is the last state in mind. The basketball team with a rough mascot association, the Utah Jazz, started as the New Orleans Jazz, before moving five years later to Utah.

Initially, according to the NBA’s page on the Utah Jazz, there were reservations about how Utah might receive the team. Now, “Utah Jazz fans have become some of the most loyal fans in the league.” This is possibly due to The Jazz incorporating some of Utah in its mascot. The black bear, common in southeastern Utah, became the official mascot of the team, ultimately creating one of the most iconically funny mascots in basketball.

The Utah Jazz Bear is known as much for the antics it pulls on the crowd as it is the cool headband it wears with every appearance. The man behind the mascot, Jon Absey, was with the Jazz for 16 years.

“The things that I can get away with and the things that other people can’t always make me laugh,” Jon Absey explains what he loved about the job in a video titled, “A tribute to the Utah Jazz Bear.”

It made the crowd laugh. However, before being people in a costume used for entertainment and before the Utah Jazz Bear was born, mascots were just human.

Originally, according to etymologist and contributor to the Oxford English Dictionary Barry Popik, mascots most commonly used to be regular people with no costume. They were typically batboys that teams believed would bring them luck during games.

Through baseball in the late 1800s, mascots began to resemble furry, feathered or winged creatures. Mascots began to entertain the crowd in between actions but soon enough they would offer a fierce competitiveness while being a cultural symbol of pride. To this day a mascot is usually a person in a costume hiding their identity, allowing viewers to suspend disbelief while they perform and pump up the crowd.

While hornets are not furry or feathered, they do take flight and they have been representing Fullerton College since its early days.

Currently, the school has Buzzy the hornet, whose interchangeable eyebrows on the newly-revealed costume can go from friendly competitor to fierce adversary in a second. Buzzy’s athletic wear allows their wings to flap freely and proudly shows off the community college’s colors, gold and blue.

Buzzy wasn’t always rocking the gender-neutral, ambiguous name. Previously to being Buzzy, our main mascot was Herbie the hornet (male) and buzzing alongside him was Henrietta (female). With the recent revision to Fullerton College’s mascot, Buzzy is as popular as ever and not an easy hornet to net, according to Spirit Team Coach Alix Plum. Buzzy is wanted at many events. Even with the assistance of wings, they can’t be everywhere at once.

“It is difficult to get a student to commit to being Buzzy,” says Plum, who used to be in charge of directing Buzzy. “Takes a certain personality.”

More than personality, it takes capability.

Alterations to the Buzzy uniform have made it hot and difficult to wear, Plum says. The person behind Buzzy is given an ice pack vest to keep cool, but it usually melts before the gig is over, weighing the already heavy uniform and making it more difficult to move and see.

“The head is heavy,” Plum says. “Movement allowed is minimal to avoid the head falling off.”

Nobody at Fullerton College wants to see the head of Buzzy horrifically severed and rolling onto the floor. In fact, it is not common for any mascot costume to be seen taken apart or non-animated. Just as it is not common to know the person behind the mask.

“You can’t talk and you’re not supposed to show your face,” Andrew Johnson, the mascot for the Houston Texans, tells ABC 13.

He went four seasons as the man behind Toro the blue bull before the team decided to identify him.

Now millions of groups and organizations participate in these traditions. Mascots trickled down to schools over a century ago, so while they strive to serve as a tentpole to a community, they sometimes create division and controversy.

Plenty of sports teams and schools have a history of portraying caricatures or negative stereotypes through their mascot and Fullerton is no exception.

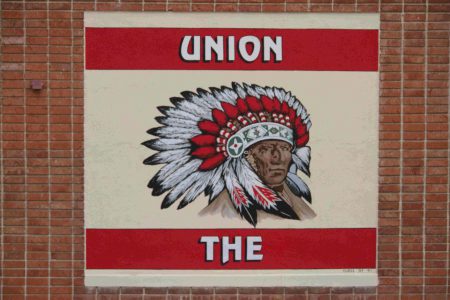

For over two decades Fullerton High School, one of the oldest campuses of Orange County and part of Fullerton College’s origins, has drawn ire from Fullerton residents over its mascot. Native American Civil Rights advocates have been petitioning for years to change Fullerton High School’s Indian mascot.

After backlash in 2001 for using traditional Native American headdresses and clothing for their mascot, Fullerton High School started using a buffalo instead. They still however are the Fullerton High School Indians.

Many teams and organizations have changed their mascots to be more respectful and culturally appropriate. Even professional sports teams have joined the cause in being more sensitive to what is socially acceptable in a mascot.

MLB’s Cleveland team used to have what most people agreed was a Native American caricature for a mascot and logo. Chief Wahoo had bright red skin, a feathered head and a goofy grin. After serving Cleveland for over a hundred years he is now retired. Similar to Fullerton High School, Cleveland switched out their mascot but kept the name and logos. Now, after about 30 years, they are the Cleveland Guardians.

A community is ultimately what makes a mascot more than a symbol for a team. What was once a good luck charm evolved beyond superstition to trust. Fans dress up as them to games, slap pictures on car windows, and prop figures on desks at work as if to show that victory is certain. Simultaneously, mascots connect us with our inner child, reminding us that, after all, it’s just a game.