It was the late ’80s when 12-year-old Alicia Rojas and her family immigrated to the United States from Colombia, with the hopes of escaping the violence that polluted the country. She had originally moved to New Jersey, where she felt her culture was not accepted.

She recalls being bullied and stigmatized by the kids in her neighborhood because of the lack of a Latine and Hispanic community. She described it as feeling “completely unwelcomed.” Later on, she and her family moved to Mission Viejo. This was where she finally felt a larger sense of connection with the Colombian and Mexican immigrant communities. It was one of the first feelings of belonging that she had felt since she immigrated to the U.S.

“Our stories of immigration were so different, but our strive to feel American or to belong was the same, ” Rojas says, referring to the way she felt welcomed by the Mexican immigrant community..

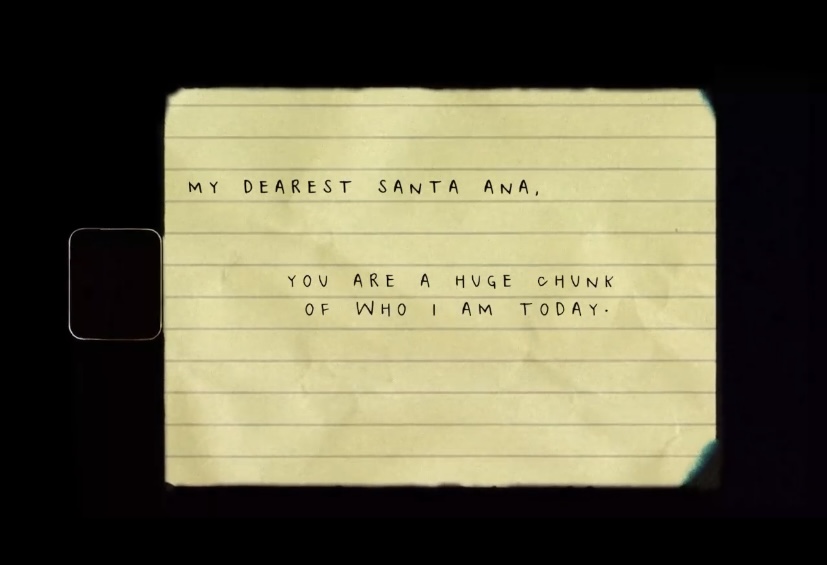

On her second day in California, in 1992, she took a trip to Santa Ana with her aunt, where she explored downtown, known as La Cuatro by the locals. After experiencing the atmosphere and the Latine culture that Santa Ana embraced, it became the place where Rojas felt the most connected. Like many other artists, this was the place where she later came to show her art.

“It was meant to be,“ Rojas says.

Santa Ana has always been a city that embraces Hispanic and Latine culture and has had a booming art scene since the 80s. The Artists Village in historic Downtown Santa Ana is home to multiple art studios and galleries that draws artists and art enthusiasts from all over Orange County.

Rojas is part of a thriving community of Latina artists from Santa Ana who use their art to embrace their culture. These artists work to empower other Latinas to keep pushing to have their voices heard and to keep the culture and history alive in their hometown, even as it is facing immense gentrification. As bigger businesses and apartment complexes move into Santa Ana, local businesses and residents are forced to move out because of the rise in prices, however, through their art they are showing the hard work that the Latine community put into building the city, the financial struggles residents are facing, and the memories that bring them together.

Rojas was in her early 20s and living in Mission Viejo, California when she started using art to express her true emotions throughout her battles with mental health and the struggles she faced growing up as an immigrant.

“I started doing art to heal,” she says.

She began by painting self-portraits that encapsulated her anxiety and stress that came from dealing with things such as immigration proceedings and having to grow up too fast. Her first paintings were made for herself and were a huge part of her healing process.

One night, she was at the Avant Garde art gallery in the basement of the Santora Arts Building and began talking with the gallery’s art director. After she revealed that she was also an artist, he asked to see her work and invited her to show the self-portraits at the next Santa Ana art walk, an event that is held the first Saturday of every month in Downtown Santa Ana.

The night of the art walk she arrived home to a message on her answering machine from the art director letting her know that one of her pieces had sold. Even though this was good news, she was faced with sadness instead.

“I remember bawling and crying because I wasn’t ready to let it go.”

After a while, the purpose of her art shifted when she and other artists began noticing the gentrification that was taking over. She began making art and murals that told stories of the Latine and Hispanic community in Santa Ana.

“My art translated from self-healing to telling our stories and preserving our history,” Rojas says.

Rojas was one of the artists in the Santa Ana Art Coalition who worked on the VIVA Santa Ana Community Mural. It was created in 2016 in an alley between Bush and Main streets in Downtown Santa Ana with the hopes of sharing the voices of local residents and preserving the history of the evolving city. The mural depicts the immigrant community of labor workers from the 1930s, Santa Ana’s historical architecture, and a painting of a paletero using a naturalist art style similar to the famous Mexican artist Diego Rivera.

(Photo by Mark Rightmire, Orange County Register/SCNG)

For Rojas, the importance of being a Latina artist is acknowledging that not all paths are equal and to find one’s own way through challenges.

In 2020, four years after the VIVA community mural, Rojas decided to lead another community mural that shared the stories of powerful and influential Latinas from Orange County.

It’s a piece called “Poderosas” located in Costa Mesa on Baker Street.

Two of the Latinas that are highlighted in this mural are Modesta Avila and Frances Munoz. In 1889, Modesta Avila was a San Juan Capistrano resident who placed an obstruction on the Santa Fe railroad track near her home because the property had been taken without her permission. Soon after she was arrested and became Orange County’s first convicted felon. Frances Munoz was appointed to the Orange County Harbor Judicial District in 1978. She was the first Latina trial judge in California.

Rojas says, “It’s important for young women and young girls to see themselves in these stories of having an example of who we can be and who we are.

Julie Leopo began her work as an artist in 2015. She was walking down 4th Street, a place widely cherished by Santa Ana residents for its Latine art, food, and community—when she realized that there were lots of changes happening in her hometown. Because of gentrification, renovations had begun and the cost of living was going up for the residents and business owners of Santa Ana. She began to reach out to the small businesses that operated on this street and ask for their experiences. This later became her story “The Voices of Fourth Street.”

“I fully started to realize that their stories were very important and they needed to be recorded because sooner or later they’d leave because they couldn’t afford rent or had no more clientele because downtown was no longer a place that Latinos identified as a place to go and shop.”

The work she did on this project eventually got picked up by The Voice of OC, a local news organization. The goal of her work, like “The Voices of Fourth Street,” is to share stories that will motivate people to have more engagement in their community and demand change, “the change that they want to see,” she says.

Leopo is a photojournalist born and raised in Santa Ana. She is the director of photography for the investigative non-profit news organization Voice of OC that covers local arts and politics. Leopo focuses on spreading news about civic life and sharing Latine stories visually through photographs.

“Latinos in media don’t have the proper coverage and I want to change that,” Leopo says.

She also does some written reporting to accompany her work.

After her story on the struggle business owners in Santa Ana were facing, Leopo did another story in 2015 about the lives of kids in low-income neighborhoods in Santa Ana, called “Summer in the City: Innocence Lost and Found.”

She reported on what their summer days looked like and how, despite the dangers that existed within their community such as alcohol usage, dangerous driving, and gang violence, the kids searched for their playtime because it was still a daily necessity to them.

“It was through their stories that inequities were highlighted in that neighborhood.”

Some of the photos in her story include a little girl painting her dog’s nails so that they can match hers and a boy posing with a fake gun in his arms.

Through her work, Leopo has encountered more Latinas being inspired to get more involved in documenting or protesting against injustices happening in their communities.

“That, to me, is really important because that just only means that there is more perspective coming in, unique perspective like Latina women in media.”

Silvia Miranda is a Latina artist whose work consists of nonfiction films and documentaries that have the purpose of empowering and sharing the stories of those who have little to no representation in the media.

She currently attends Chapman University and describes herself as a visual storyteller who focuses on film as well as photography.

Miranda is currently focusing on documentary filmmaking, which isn’t always easy for women in the film. A study done by USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative found that out of 1,447 directors that made films between the years 2007 and 2019, only three were Hispanic women.

“My purpose is to truly uplift stories and bring to the forefront stories of queer folks and people of color,” says Miranda.

One piece that is important to her as a Santa Ana resident is the short film “El Carrito.” It is an observational piece that follows a street vendor through his day selling on La Cuatro in Santa Ana.

The short film is centered around José Guadalupe Rodriguez, who sells Mexican snacks such as esquite and fresh cut fruit topped with spices known as fruta preparada. It shows how his business has remained in the center of Santa Ana for the past 20 years despite gentrification pushing local business owners in La Cuatro away.

“It was truly an incredible experience because I had grown up always going to La Cuatro, and I always saw José, and I think that he is one of the only people and businesses that has remained the same,” Miranda says.

Miranda’s work brings in themes from her Mexican American heritage. Just like the film “El Carrito,” most of her work has some sort of Mexican representation.

Miranda says, “In everything I touch and everything I create, there are always traces of my Mexican heritage.”

Many of her films display multiple Mexican traditions such as baile folklórico, altars for the Day of the Dead, and traditional Mexican clothing.

Miranda is a proud Latina artist with immense determination to do what she loves and to spread the voices of those who are not always heard. Miranda’s experiences as a Latina woman make her work one of a kind and more difficult at the same time, but she is determined to continue doing what she loves and make a change for the Latine community.

Reflecting on the struggles she and other artists have faced, Miranda says, “In a really dark and twisted way it really does bring us closer because we share a different bond because we’ve gone through the same experiences of not being taken seriously.”