At a Placentia-Yorba Linda Unified School District board meeting in the spring of 2022 parents, students, educators, and board members gathered to debate a potential ban on critical race theory. “You see what this education has provided—all of these little activists arguing for racism. These children are arguing for racism,” said John Barkley, an attendee at the board meeting. The audience cheered and clapped as he made his remark. The “little activists” he spoke of are students from the school district attending the same board meeting, and the “racism” they are arguing for is the teaching of critical race theory, because they believe it is essential to an honest and inclusive education.

On April 5, 2022, the Placentia-Yorba Linda School Board passed a ban on critical race theory from being taught in their district, but cities in Orange County aren’t the only locations where critical race theory in K-12 is up for debate. Across the nation, hundreds of cities and school districts are implementing regulations against CRT. Some school districts and parents are defining CRT as harmful to students and demanding that it be banned, while other parents and students are fighting against this narrative by claiming it is an essential part of education. Educators and scholars argue that it is a topic that isn’t taught in K-12 schools at all, and the controversy surrounding who is right and who is wrong continues to be a topic of discussion.

“There is so much backlash against critical race theory by people who don’t know what critical race theory is,” says Danae Hart, an African American Studies professor at Fullerton College.

Critical race theory was adopted in the 1970s by a group of legal scholars including Derrick Bell, Richard Delgado, Cheryl Harris, Kimberlé Crenshaw, and many others. It was created to challenge the argument that the structures that are in place in America, such as medical systems and criminal justice departments, are essentially “colorblind” and that they were created with equal opportunity. It theorizes that racism goes far beyond prejudiced beliefs or actions from individual people, but that racism is also embedded into the structures used today. CRT explains that these structures discriminate against people of color by not upholding the same standard that would be used for white people, in turn, continuing the cycle of inequality for African Americans and other people of color in America.

“Critical race theory is looking at those big systems, it’s looking at systemic racism and how it operates,” says Hart.

Some school board members, parents, and students don’t agree with the ideology of critical race theory, and the speculation that it was being taught to their kids in school ultimately sparked the controversy of CRT being taught in K-12.

“Critical race theory is a theory, and it basically puts one group as oppressors and one group as the oppressed, and to me, it was a form of reverse racism,” says Leadra Blades, vice president of the Placentia-Yorba Linda School District, when asked what critical race theory is.

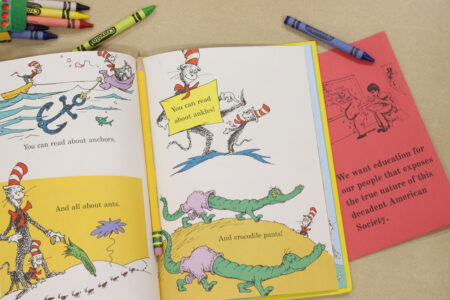

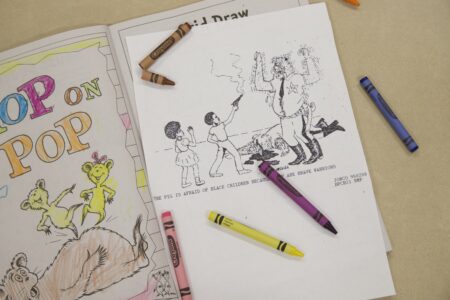

According to Blades, parents and students would reach out to share what was being taught in their classrooms. Some examples were teachers handing out worksheets about the founding fathers and Abraham Lincoln being racist, but scholars are arguing that these common examples are not critical race theory because critical race theory doesn’t look at racism on an individual level. “That is just folks’ individual opinions and that is not critical race theory,” says Hart.

Blades also alleges that teachers in her district were telling white students to leave their white privilege at the door as they walked into the classroom. Parents did not approve of this method of teaching and the idea of CRT being taught to kids became an immense issue. Blades states that board members would be “inundated” by emails and phone calls from parents and students reaching out to speak on their concerns and dissatisfaction.

A parent, who chose to only go by Brent, said at the April 2022 board meeting, “Last year, my daughter’s history class was CRT influenced all year long. The main theme: white people are bad.”

Other parents don’t believe the view that CRT makes white people seem like the “bad guy.” “Not one of my kids feels bad for being white, nor do they feel that Placentia-Yorba Linda School District has tried to make them feel bad for being white,” said Carrie Burnell at the March 23, 2022 board meeting in opposition of the ban.

While critical race theory does include the study of whiteness, white privilege, and the idea that systems are racist towards people of color because they cater more towards white people, it doesn’t refer to white people directly being racist or bad because of it.

Cheryl Harris, one of the developers of CRT, wrote in her June 1993 article, “Whiteness as Property,” that whiteness holds power and privilege because America was built for white people to succeed and that although white people can still struggle, they won’t face the same struggles that Black people face as a result of racism.

“Nevertheless, whiteness retains its value as a ‘consolation prize’: it does not mean that all whites will win, but simply that they will not lose, if losing is defined as being on the bottom of the social and economic hierarchy – the position to which Blacks have been consigned,” Harris writes.

In opposition, other parents believe that CRT should be taught regardless of whether it makes white kids feel bad or not. At the March 23, 2022 board meeting, Brooke H. said, “If my kids are old enough to experience racism, then your kids are old enough to learn about it.”

Another common argument made by parents and school board members who oppose CRT is that it is forcing their kids into certain stereotypes that could cause feelings to be hurt and a divide between students.

“I don’t understand why anyone would embrace a theory—because critical race theory is just a theory—of trying to make people into oppressed or oppressors,” says Blades.

At the April 5, 2022 school board meeting, Blades presented results from a survey taken by the Orange County Board of Education from adults in the Placentia-Yorba Linda Unified School District. The results showed that out of all the survey participants, 51% believed that critical race theory has Americans separated by race, as oppressors and victims. Additionally, 75% of respondents believe that CRT should not be taught in K-12.

Critical race theory is made up of other concepts such as structural racism, intersectionality, microaggressions, and the idea that race is a social construct, and although all of these concepts highlight the theory that racism is still a large part of today’s society that harms people of color, it wasn’t developed to make people of color feel oppressed. It was developed to understand and challenge ways that people of color continue to be harmed by being treated unfairly.

When looking at the statistics of people in Placentia and Yorba Linda that view CRT as bad, divisive, and an ideology that should not be allowed in schools, it is also important to take into consideration the impact that political affiliation and race play into these beliefs.

A report done by The COVID States Project found that 23% of white respondents agreed with critical race theory. This percentage is low when compared to the 42% of Black respondents that support CRT. The study also found that white republicans had “exceptionally low support” when it came to CRT.

Since 2020, Republican politicians and media outlets have described critical race theory as being the cause of a divide that points blame at white people for the struggles that people of color face and that it further creates racism.

“There’s this fear that if we talk about race, it’s somehow making racism exist as if it doesn’t already exist within our society,” says Hart.

Students in the school district who strongly oppose the ban on critical race theory say they view it as censorship that is only harming their education and students of color.

At the November 16, 2021 board meeting, Magdalena Aparicio, a student at Yorba Linda High School, showed her disapproval of the proposed ban by recounting an incident where a poster that stated “your dad is my gardener” created to mock Hispanic students during a football feud made her angry. “As a Hispanic student, and a child of Mexican immigrants, I sat in my classes as my classmates debated my right to be angry,” said Magdalena. “We must have uncomfortable conversations or incidents like this are more likely to occur and swept under the rug.”

The ultimate decision to ban critical race theory made by the Placentia-Yorba Linda Unified School District created backlash for the district. A year after the vote was made, parents and scholars are still expressing their disapproval of the ban at board meetings and asking for the ban to be removed. A major event that was set into effect after the ban was Cal State Fullerton’s decision to pull all student teachers out of the school district.

On October 17, 2022, Cal State University, Fullerton announced that they would no longer be placing student-teachers in the PYLUSD. This was due to student-teachers feeling they were not getting enough clarity on whether ethnic studies, needed for teacher preparation, could be taught in the district.

PYLUSD isn’t the only school district that has taken action to ban critical race theory. According to CRT Forward, an initiative that was launched by the UCLA School of Law, as of the first quarter of 2023, nearly 200 local school districts across the United States have introduced measures to ban critical race theory.

While school boards continue to take measures against critical race theory, scholars say that it isn’t taught in K-12 schools at all, but instead is only formally taught and discussed in colleges and graduate schools because the topic is too complex.

“In K-12 education, in the curriculum, there’s really no discussion of theory in any subject,” says Hart.

Christopher Emdin, a professor and author who specializes in urban education and curriculum, said in an interview with Wisconsin Public Radio that critical race theory is not being taught in K-12, but instead, a curriculum is being taught that teachers feel appeals to the diversity of their students.

The way a K-12 teacher K-12 would teach their students a lesson on redlining and racial housing covenants differs from how a college professor would address these topics.

According to a sample lesson from the California Department of Education, this lesson would be taught by defining the terms, having students read the book “A Raisin in the Sun,” by Lorraine Hansberry, and then having the students analyze how African Americans faced housing inequalities in the past and how they still face these issues. The sample lesson states the objective of the lesson would be to “Engage and comprehend contemporary language being used to describe the current housing crisis and the history of racial housing segregation.”

This lesson would not be used by a college professor who is teaching critical race theory. A lesson plan on racial housing covenants created by California State University, Northridge only uses direct historical events to teach the lesson. It includes facts about white people at the time protesting African Americans living in the same neighborhoods as them because they viewed African Americans and other races as inferior. These are facts that are not mentioned in the K-12 lesson plan; college lessons on CRT concepts are taught with more factual examples of the realities of racism.

Aaliyah Skipper, a Fullerton College photography student, enrolled in an ethnic studies course in her second year of college, which is where she learned about critical race theory. Skipper was shocked by what she was learning since it had been completely new to her.

“When I was in high school, history wasn’t directed for me, for kids like me, for POC,” says Skipper.

Skipper attended El Dorado High School in Placentia and in those years, the history that she learned didn’t give her enough information about her culture’s background or the American structure and how it could affect her. When it came down to learning the history of her own race in America, Skipper only recalls learning about slavery and how they were colonized by the Europeans.

Now that Skipper is in college, she is learning more CRT concepts, such as systemic racism. A topic that she learned about was that statistically, Black women receive fewer pain medications during labor and postpartum because of the stigma surrounding Black women having a higher pain tolerance. A study done by doctors at Northwestern University found that although Black and brown women report high pain levels postpartum, they receive fewer amounts of morphine than white women.

“This is so far in the future, but I’m so scared to have kids,” says Skipper. “I wish I would’ve learned about it sooner. It would’ve changed my decisions, how I see myself, and how I see the world.”

As ideologies such as critical race theory are being disputed and banned across the country, scholars and activists are worrying about what it could mean for history, education and social justice movements that uplift people of color.

“It’s really harmful to see that something that was so empowering for folks, like ethnic studies and African American studies, to be challenged in such a public way,” says Hart.

Although these are times when practices and heavily developed theories like CRT are under attack, scholars such as Hart still have hope that there is a bright side to the controversy: “Banning critical race theory, the positive side is that more folks are talking about it and more folks are looking into what it is and learning about it.”