At first glance it’s just a house in Fullerton, California—but step inside and you’ll find a shrine to one of the most consequential and under recognized milestones in civil rights history. The walls are jam-packed with faded photographs, brittle newspaper clippings and an impressive haul of awards. This is where Sylvia Mendez lives, a woman whose life story is etched into the very DNA of America’s fight for equality.

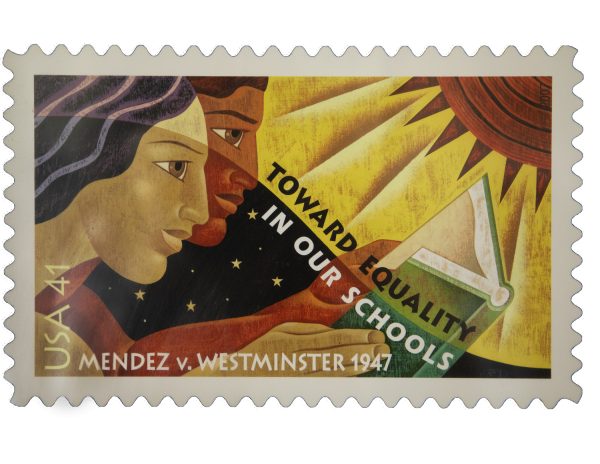

Sylvia is perhaps best known for her role in the landmark school desegregation lawsuit Mendez v. Westminster. Decided in 1947, it ruled that school segregation was unconstitutional in California—seven years before Brown v. Board of Education desegregated schools nationally in 1954. Yet behind this historic legal victory is a deeply personal family journey, marked by Sylvia’s father’s unrecognized sacrifices and the often-forgotten moments in history in the fight for civil rights. 80 years after Mendez v. Westminster was filed, these layered histories remind us that the struggle for equality is ongoing.

In 1944, eight-year-old Sylvia was denied entry to a “white school” in Westminster, California because of her Mexican heritage. Her father, Gonzalo Mendez refused to accept the injustice.

“He wanted us to have the best education, the opportunities he was denied,” says Sylvia.

What followed was a legal battle that forever changed the California education system. In 1945, Gonzalo, along with four other Mexican American families—the Estradas, Guzmans, Ramierzes and Palominos—came together to file a class-action lawsuit against four Orange County school districts alleging that Mexican remedial schools didn’t give children equal access to education. Their attorney, David Marcus, argued that segregating Mexican American children in California violated the 14th Amendment. This case challenged segregation practices in schools across the state. In 1946, Judge Paul McCormick ruled in favor of the Mendezes and the other families and declared segregation unconstitutional. The following year, the decision was upheld on appeal. For Sylvia, the victory was life changing.

“It meant I could finally go to the ‘white school,’” she says. “But it also meant so much more. It was a step toward equality for all children.”

In 2011, President Barack Obama awarded Sylvia the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Standing in the White House, she recalls being overcome with emotion and crying, thinking of her mother and father, the two unsung heroes who had sacrificed so much. Evennow, in the same house where her mother passed away, Sylvia keeps the memory of her mother alive through her attempts to keep plants blooming—a passion her mother had

Raised by Gonzalo and Felicitas Mendez, Sylvia grew up in a household defined by hard work and a commitment to community. Gonzalo was originally from Chihuahua, Mexico, and Felicitas hailed from Puerto Rico. Before moving to Westminster, the couple owned a cantina in Santa Ana and bought multiple houses, renting some out for extra income.

While many are familiar with the success of Mendez v. Westminster, few realize the heartbreak that Sylvia’s father, Gonzalo, endured. He sold a cantina he owned in Santa Ana and multiple properties to fund the legal battle to get his children—Sylvia, Gonzalo Jr., and Jerome—into the best schools. Yet, Gonzalo did not live to see widespread recognition of his pivotal role. He died in 1964, at just 51. It wasn’t until 2003 that the case gained more recognition when the documentary “Mendez v. Westminster: For All the Children/Para Todos los Niños” was released.

Sylvia shares how people often brushed off her father’s story, diminishing the sacrifices he made for the historic case.

“Nobody believed him when he said he fought the case,” she says. “They didn’t even know about it. They didn’t believe it.”

According to Sylvia, the disappointment took a toll on his health, leaving him financially drained and emotionally depleted.

Initially Sylvia didn’t envision herself as the public voice of Mendez v. Westminster. She worked as a practicing nurse, accustomed to hospital wards, not podiums or speaking arrangements. But on Felicitas’s deathbed in 1998, she urged her daughter to share their family’s role in ending segregated schools in California. Sylvia remembers the anxiety, shaking legs and trembling voice during her very first presentation at a local school in 1999, at the age of 62.

“I was so scared. But the students said, ‘Don’t worry, just tell your story.’ And that gave me the courage to keep going,” she recalls.

In the decades since, Sylvia has spoken at schools and colleges nationwide. She shows photos of the cramped “Mexican” school that she and her cousins had to attend, while a much nicer “white” school stood mere blocks away. She also shares how her father’s heartbreak motivated her even more to ensure his story isn’t forgotten.

“They lost everything during the case,” Sylvia says. “They gave up their business and their savings, even their own security, because they believed in what was right.”

Today, at 88, Sylvia is a great-grandmother; her home is filled with children’s laughter, alongside the coughs and colds that inevitably follow. “They bring me constant sniffles,” she jokes, but she clearly relishes every moment with grandchildren and great grandchildren. She settled in Fullerton over 60 years ago, in part for its proximity to her nursing career in Los Angeles.

Despite personal speaking tours and countless invitations, Mendez v. Westminster has remained unknown to many. But in September 2024, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill 1805 into law, a bipartisan effort requiring that the story of the Mendez family—and the other plaintiffs—is featured in history and social studies classes throughout California.

The law also compels schools to cover the intersection of immigration, housing restrictions, anti-Mexican discrimination, and the World War II era incarceration of Japanese Americans that shaped so much of California’s 20th-century racial climate.

Jodi Balma, a political science professor at Fullerton College, teaches the Mendez case in her honors government class. She underscores that this landmark lawsuit “reminds us of the fight for civil rights wasn’t confined to the South. It was happening right here in California.”

The Museum of Teaching and Learning (MOTAL) in Fullerton, California, led by founder Greta Nagel, has developed an exhibit called “A Class Action: The Grassroots Struggle for School Desegregation in California.” Nagel’s exhibit immerses viewers in the sights, sounds, and raw truths of segregated “Mexican” schools—rusty desks, soap bars once used to punish children for speaking Spanish, and a stark 48-star American flag from an era denying civil rights to so many. “When people see these artifacts and hear the stories behind them, it becomes real,” Nagel says.

“It wasn’t just one family or one lawyer,” Nagel says. “It was a community effort.”

One of the stories highlighted in the exhibition is that of the Munemitsu family. The Munemitsus owned the farm in Westminster that the Mendez family leased in the early 1940s. During World War II, the Munemitsu family was forced into an internment camp in Poston, Arizona, like many Japanese Americans. Janice Munemitsu, the author of “The Kindness of Color,” says a banker at Garden Grove First National Bank, introduced Gonzalo to the Munemitsus and arranged for him to lease the farm from them, so it could be tended by a trusted renter until they could return.

Both Sylvia and one of her aunts recall trips to the Arizona desert with Gonzalo to pay rent in person.

The Munemitsu property provided the Mendez family with a livelihood during their monumental legal battle against school desegregation.

“The connections between these stories are profound,” Nagel says. “They show how different communities faced discrimination and how they supported each other.” The relationship between the two families did not end in the 1940s. Sylvia wrote the foreword to “The Kindness of Color,” and both families appear at conferences, book promotions and speaking engagements to highlight their story of solidarity.

Sylvia says the fight for equality in education is far from over. “We’re more segregated now than we were back then,” she says. “Not by law, but by economic and systemic barriers. We need to ensure every child gets a good education, no matter where they live.”

In Orange County, the 2022-2023 California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP) data shows that only about 38% of Latino students met or exceeded state English Language Arts standards, compared to around 65% of white students. In math, the gap was similarly wide, with 34% of Latino students meeting or exceeding standards versus over 60% of white students.

According to a 2020 study by the nonprofit Ed Build, predominantly white school districts nationwide receive about $23 billion more in total funding than equally sized districts serving mostly non-white students. The source of the disparity often lies in local property taxes and historical redlining practices. Redlining is a discriminatory practice that began in the 1930s, where banks, lenders and government agencies systematically denied mortgages, loans and other financial services to people living in predominantly non-white neighborhoods. These areas were marked with red lines on maps, signaling them as “high risk,” which suppressed property values, limited economic opportunities and entrenched racial segregation.

Jodi Balma, a political science professor at Fullerton College points out that even in Orange County—often perceived as affluent—pockets of lower-income communities “experience more frequent teacher turnover and a scarcity of classroom aides, compounding disadvantages for students who need support the most.”

Balma stresses that acknowledging these disparities is the first step toward closing the gap. “People often think the battle for school integration was fought and won in the 1950s and 1960s,” she says. “But current data shows we still have a way to go in providing students—regardless of race or zip code—an equitable education.”

Standing in her Fullerton home, surrounded by trophies and testimonies, Sylvia hopes that each retelling of her story plants a seed—just as her mother once planted roses in the garden—for people to be inspired to continue fighting for equality in education.

“History is personal,” she says. “My parents gave up so much for a chance at fairness. It’s important we share these memories, so future generations don’t take them for granted.”

This appeared in the Summer 2025 print issue of Inside Fullerton.