On our family computer, there are very old photos saved of past relatives. The great, and great-great grandparents I never met, mostly digital folders with their faces. When I see them, I smile as if I’m staring into a mirror. I look at the velvet apparel they wear that was most likely colorful, though black and white. They wear long skirts, and their hair tied back as they looked stoic and serious with the Arizona landscape behind them. I could tell they wore jewelry although it appeared faint. Along with those photos, I have boxes of printed photographs of my family, some of old friends that came and went and pictures of myself.

There are a few photos of myself that my family framed on the wall in the living room hallway that I pass by multiple times a day. There’s one of me when I was eight years old in a 50s poodle skirt Halloween costume, another in a Boy Scouts outfit at six, and one in traditional Mexican clothes. A white floral blouse and a bright red skirt. It’s a definite fashion statement. I look at it with pride. I come from generations of hard-working people, on both my mom’s and dad’s side. I’m a fourth-generation descendant of Latino immigrants, 25% Cajun Creole and 25% Navajo.

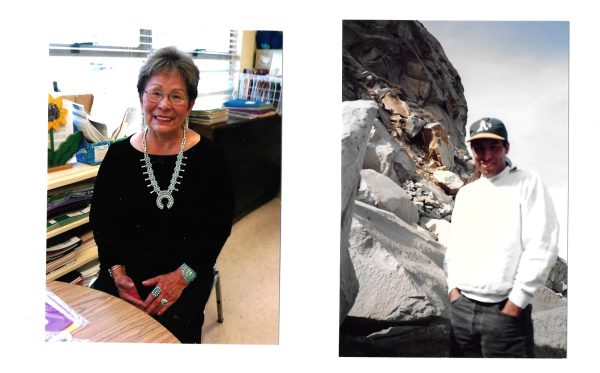

I always embraced my Cajun-Creole and Latino roots. But there is one part of my heritage I always struggled to connect with and felt embarrassed of: my Native American side. When I was in first or third grade, my grandma, who is 100% Navajo, born and raised on the reservation, came to my class to talk about our heritage. We were learning about Native American history and their customs. My grandma wore a black long-sleeved shirt and pants, to accentuate the bright turquoise wrist cuffs, rings, necklace and earrings she wore. What she brought to share to the class was nothing physical, but her wisdom. When I went up in front of the class with her and she asked me to say my Native name, I said it so quietly, too embarrassed to talk about it. I didn’t want to say my Native name or wear the colorful turquoise she adorned me with. I felt it made me standout out too much. My classmates looked at me like I was a stranger when I said my name, and if not that, then definitely confused.

A part of me wants to justify being embarrassed, as though it was a form of stage fright, but my feelings say something else. I was embarrassed to be Navajo. I didn’t want to be labeled as different or be judged, I wanted to be like every other kid.

Before I moved to the home I live in now, I lived in a neighborhood with a lot of kids. My neighbors across the street had sons that went to the same school as me. Dogs were always on the lawn, and my dad and I would go bicycling down the hills. During the holidays, decorations were displayed on the neighboring houses, and trick or treating on Halloween felt like winning the lottery with how many kids were lining up at doors.

I didn’t want to understand or learn about being Native. I didn’t even know the name of my people, the Navajo, in their own language—Dinè. That was who my father was, my grandmother, but not me. The other ethnic identities that I surrounded myself and was familiar with were Cajun-Creole and Latino with the food my mom and dad cooked or the music I heard when we had family events. Outside of my family, the only Native representation I saw was in Western movies.

In high school, my class was assigned an end of year Women’s History project, a precursor to the dreaded finals week. We needed to ask a family member about history—not the history they remember learning or how they were taught, but their personal story and their culture. The few friends I had shared my Native heritage with suggested I ask my grandmother. It never occurred to me to ask her. It took me two days to finish, but working up the courage to even ask her something like this so out of the blue seemed a bit strange. After all I lived a normal life, going through classes, and when learning again about indigenous history, I took the notes, but mentally, I was checked out.

Recently, my pops and I were in the kitchen late at night, sitting at the kitchen counter after I washed the dishes. I had built-up nerves asking about his relationship to being Native, and I figured after the good meal he cooked, I could ask. He told me, without hesitation, that he understood at a young age that his half-Indigenous blood connection to the Navajo tribe was not very common in his neighborhood of Whittier, California. “I’m just glad, proud that I have that Native link,” my pops says.

He pulled out some pictures from when he was around 20 years old. He had long hair down past his chest and wore worn-out dark jeans, a white sweatshirt and a yellow and blue trucker’s hat with a bold white “A” on it. He only mentioned once or twice before that at that age he would go to visit my great grandmother on the Navajo reservation, where his mom and grandma grew up. He didn’t go into too much detail about how it looked, but I could imagine the dry and rocky canyons, pale cloudy blue skies and the sun’s bright rays, differing from the world than the one I grew up in.

My grandmother spoke to my pops in Navajo when he was a child and he was able to communicate with her, but when it was time to enter kindergarten at the Catholic school, nearly a two minute drive from his childhood home in Whittier, my aunt, uncle and dad shifted to primarily speaking English in school.

“I wish I could have been reinforced by your grandmother,” my pops says. “But I think at that time also, you know—I don’t know if we’re embarrassed to speak it when we were little or around where we live, but we told her, hey we don’t want to talk in Navajo, we want to talk in English.”

Hearing my dad say this—that there was also a time he was embarrassed to be Native—made me feel like we were in the same boat. I suddenly felt less alone.

I thought I was the only one in the family who didn’t understand Navajo culture and traditions, but even my pops somewhat struggled with it. Trying to understand the culture for him is “an ongoing process,” he says.

A year ago, when I was 20, at a family function the day before a powwow, when I saw my grandma needing help walking to her car, it hit me, intensely, that she is a living, breathing, walking woman full of culture and stories. She was getting older, quicker than I’d like to admit. The next day I was going to University of California, Los Angeles, and I would see people dancing, selling authentic Native clothing, jewelry, decorations and speaking not only Navajo, but other Native languages. My grandmother would be in her element, and I realized that if I could not understand this culture through her lens, then how could I ever see it through my broken ones? That thought terrified me and made me rethink everything.

After that day, I grabbed that photograph of my grandmother in that classroom, hardly crinkled despite having been in my drawer for so long. Her hands are folded with beloved turquoise pieces she owned all her life. It made me so sad I wanted to cry. I was so ashamed, more at myself than anything. At that moment I just wanted to look away, put it back in my drawer and let it collect dust again. But I knew I couldn’t put it away again. My own grandmother, who taught my dad to speak Navajo, and has seen more things than I ever will—she wasn’t just someone to remember in a dusty picture, she is here now, and all I need to do is look at her, talk to her and listen.

Instead of running in moccasins of heritage, I ran around in department store sneakers. I spoke in a tongue that many can understand instead of learning a language tied back to generations. The vibrancy, dancing and music of my family were replaced by pop songs that everyone else listened to.

I thought, as I stared at that photo, about how many years I wasted, stuck in embarrassment. As grim as it was to think about the painful truth—I won’t have my grandma around forever. I still had a chance to change things.

Now, I go to visit my grandma in the same house in Whittier, the place she’s always lived in. After work on some weekends when I would have gone straight home, I’ve begun to ask about the Navajo people. It started in small increments until she opened up more and more–about life on the reservation, the jobs she had and how she met my grandpa and her family.

I started to record our conversations, so that I can always remember. Every time I enter her home, I see the black-and-white pictures on the wall of her and all her siblings in traditional Navajo clothes. I pass by the white, turquoise, amber and black painted pottery on the shelves, untouched and a little more vibrant now.

From those conversations I’ve started to write poetry and shown them to my grandmother. It makes me happy when she smiles and asks to keep them.

Even though I’ve never met my great-grandmother and may never know the culture to the extent that I should, I see the pieces of my family history like a puzzle, forming a much bigger picture. My dad is a part of that, and so am I. The same blood flowing through them, now runs in me.

(Nadine Baquiran)

In the spring of 2024, I took an Introduction to Native American Studies class so I could keep learning. While doing research for my assignments, I enjoyed learning not just history, but my history. I found books and museums showcasing portraits of the Navajo, Dinè, what we call ourselves. It means “the people” in Navajo, and a way to signify and present our heritage. I saw the Dinè people on the reservation with ceremonial blankets on display and it made me feel like I was home. I had always been insecure about my crooked nose, but then I saw it on so many others in those portraits, and I felt I was a part of something bigger, something important.

I recently asked my dad why he wanted to grow his hair out after he retired, knowing that the Dinè kept their hair long as a physical representation of who they are. “That’s a part of your culture, and that’s always going to be with you,” he says with a big grin on his face. “In that instance you know you’re a part of that chain, that circle from ancestor to descendant. It was something fun to see.”

The poetry that I write is a love letter to Dinè, and to the version of myself whose face once flushed when I had to speak my Navajo name. I was never an outsider, and though I let myself feel that way for a while, the severed ties of the past were woven into a stronger thread.

My Dinè family saw the same skies and lived under the sun. When my dad’s hair is long, I’m positive he will braid it. As for me, I’ll lace the moccasins that I wouldn’t wear, and when I do, the first thing I will do is dance.

This appeared in the Summer 2025 print issue of Inside Fullerton.