Sheer fear engulfed my grandfather, as rain and machine gun fire tore through the air with endless rage. The mud was so tenacious it was difficult to maneuver through it as the enemy seized with intentions to open fire.

“See to the captain first!” my grandfather exclaimed, laying on the ground with a bullet wound in his knee. His captain had been hit in the throat, shoulder and stomach. He knew he didn’t have much time. American medics saw to the captain while the Germans launched a counter attack. Three men were taken prisoner and one killed. There wasn’t much time. The medics had to leave my grandfather and the captain to get more help. Time passed as my grandfather laid there with a raincoat blanketed next to the body of his motionless captain. They had to remain perfectly still so Germans would believe they were dead.

My grandpa was a gentle man who loved the simple things. My memories of him are scattered but sharp. I remember him drawing cartoon characters for his grandkids like Donald Duck and doing his impression to go with them, carrying chilies in his shirt pocket so he can have a little more spice with his food and whistling during any task. This was Grandpa.

But there are other memories, too. The way he would jump whenever I shouted “Hi!” to him in my high-pitched voice and the way he would jump with any kind of loud noise, July 4th would always startle grandpa. That was the shell shock. It became a part of him he couldn’t shake. I would always say “Oops, sorry grandpa,” and we would share a giggle. I never asked grandpa why he would startle when I was young, not until I was older I understood. There is a main facet of my adolescence that I regret the most, it was taking the time to talk to my grandpa. The eagerness to go and play could have waited. From the few times I did stop and listen, my grandfather had so much history embedded in him.

Years have passed, and life has not slowed down. Time, I am afraid, is limited. On my lap sits a box filled with documents that my grandpa passed to my father. Inside are scraps and images of all those stories. All I need to do is piece them together, to listen to him now.

I hesitate to open, my fingers are gently grasping the latch of the box. Acquiring the ability, I open the box and the smell reminds me of old books that have been neglected for quite some time. I look at the delicate brown newspaper clippings and military documents, and I am afraid it will crumble in my hands. Emotions of regret and saudade intensify as I pick them up, one by one, to learn about the man who I called “Grandpa,” but before that was World War II Army Sgt. Maj. Henry Cervantes Falcon: Blue Devils, 88th Division of the 350th Infantry of the United States of America.

It was Dec. 7, 1941: Pearl Harbor. When my grandfather saw the news, he wanted to enlist the very next day in the army. However, the age limit was 21 to enter war. The next year, on Nov. 11, 1942, the United States reduced the draft age to 18. Shortly before, my grandpa received a draft letter from President Roosevelt, and on Oct. 6, 1942, he was inducted into active service.

I read through an interview my aunt did with my grandpa in 2008. As I read, I can hear his voice coming from the page. This interview was for my grandfather’s Blue Devils-themed 88th birthday since he was in the 88th Division.

The Blue Devils 88th Division arrived overseas with roughly 14,000 troops on the ship Liberty on May 1, 1944, 17 days after sailing out from Camp Patrick Henry in West Virginia. They trained in Casablanca, Morocco and Oran, Africa before sailing for Italy’s Amalfi Coast.

In Naples, the division received guns, ammunition and British Helmets to fool the enemy. My grandfather and his division were the first American soldiers to arrive and march through Rome on Jun. 4, 1944, 15 months before the end of the war in Europe.

Hidden within the bookshelf, I rediscovered from my father a book called “Blue Devils,” by Renzo Grandi and Valerio Calderoni. I recognize those names — old friends of the family. They conducted interviews with remaining soldiers of the 88th Division in 2009, and my grandfather was among those men who got to tell his story.

My grandfather’s company captain had received an order to take on Mount Acuto in Italy on Sept. 25, 1944. It was pouring rain as it became anything but a friend to assist the American soldiers in battle.

Up the mountain, my grandfather went with his crew and captain. They saw a white garment in the distance that appeared to be German soldiers waving a motion of surrender. Or so they thought.

The captain stepped out to see if it was clear to keep moving forward when machine-gun fire triggered. To the ground the captain went as bullets tore through the air. American soldiers fired back, leaving my grandfather to skid through the thick mud to get to his captain. That’s when a bullet crossed and hit him in the right knee, close to his shin. With the adrenaline coursing through him, my grandfather clawed his way through the mud to reach his captain.

He lay there, disoriented, thinking only of saving the life of another. No blood yet was shown on my grandfather’s ripped pant leg, just white bone. The medics gave my grandfather a morphine shot in his chest for the pain. He and the captain weighed too much for the medics to lift alone, so they left to seek further help.

My grandfather passed out and when he woke up he felt his back was soaked, hazed by the situation thinking it could be blood. He took off his belt and strapped it around his upper thigh to stop the bleeding and lay back stone still until help finally arrived.

When help finally came, it wasn’t an easy escape. The men were carried away amidst counterattacks, and my grandfather fell off the stretcher multiple times because of the slick mud and rain. He was transported from hospital to hospital, and between morphine injections, he woke up in Florence and then in Naples. Later, he passed through three different American hospitals.

He never learned what became of his captain.

My grandfather rarely spoke about that day. He refrained from talking about the war but would have conversations when approached about it. But he never missed the reunions for the Blue Devils 88th Division. In 1980, he and my grandmother Helen were at one of those reunions when she called out, “Isn’t that Ed Maher?” My grandfather looked up, and there was his captain. My grandpa thought his captain died that day considering his wounds. Maher had a slight head tilt due to being shot in the neck. The two locked eyes, and without any hesitation made their way for each other, finally hugging for the first time since that pivotal day up on the hills of Mount Acuto.

After they reunited, my grandfather and Captain Maher would call each other every Sept. 25, the day they beat the odds and survived a battle that would taunt them evermore. They would always recall the events that happened including the fake German surrender of machine gunners.

I fiddle in my hand a belt buckle my grandfather wore frequently, “88th Infantry Division Association” it says, with the Blue Devil logo, that looks like a blue first aid cross. The gold is fading into gray due to wear and tear. Chips and cracks are embedded into the embroidery as I think of the stories of what my grandfather went through in the pouring rain.

My grandfather wasn’t the only Falcon serving in World War II. My grandfather was in the Army, my uncle Rudy was in the Marines and uncle Angel was in the Navy.

Rudy, my grandfather’s little brother, Private Rudolph C. Falcon, was a Paratrooper for the 101st Airborne Division that was nicknamed the “Screaming Eagles.” The 101st Division was one of the first airborne divisions along with the 82nd. Both were treated as experiments since World War II was the first war paratroopers would enter.

A specific story my aunt shared with me that my grandfather told her, was about the time my uncle Rudy surprised my grandfather who was based in Italy at the time. It was Mother’s Day and they both had gone out to get a card for their mother, my great-grandmother Delfina. They both playfully fought on who was going to be the one to sign it first until they both came to a conclusion. Right before departing from one another, my grandfather told my uncle who was already boarded on the bus back to his base, to fix his tie as he motioned with the gesture.

Those were the last words my grandfather said to his little brother.

Uncle Rudy was killed in action on Oct. 7, 1944, in Holland. He died only a few days after my grandfather got wounded in Italy, so my grandfather didn’t get the news until a year later. When my grandfather went on leave he found out the news of his brother and did not return to base when expected too he went AWOL for 22 days in search of his brother. This AWOL was dismissed since it was a personal matter.

These are the sentimental values, stories I hold close as I search my family history. I gain a little more knowledge into the life of my grandfather and what he endured during his war years. He was the only one to receive the body of his brother, but not until five years later, when my uncle was finally brought home since he had been buried in Holland.

I hold in my hand a tiny folded pouch of scuffed and torn black leather, with the fainted words “For God & Country” etched on it. In it, there are two saints, whose faces I cannot make out. I pull from the pouch a miniature bible no bigger than a half-dollar coin and open to the first morning prayer, “O My God, my only good, the Author of my being, and my last end; I give Thee my heart. Praise, honour, and glory be to Thee for ever and ever. Amen.” This miniature Bible was recovered from my uncle Rudy. I cannot begin to grasp as I hold a little piece of him that his fingers once touched, what it witnessed. It dawns on me, I might have read the last prayer my Uncle Rudy recited the day he perished.

Family meant a lot to my grandfather. He loved his wife, my grandmother Helen. She was definitely a strong woman, very feisty with a heart of gold. I always think I would have grown to be a strong individual if she was alive during my adolescence.

My grandfather was dating my grandmother while he was at war, and he wrote to her a lot while abroad. I came across an old picture of them sitting on a bench, my grandpa embracing my grandma, almost as if she is listening in on his heartbeat. He is in his Army attire and my grandma with her 40s hairstyle and a long coat over a dress; she was so elegant. She loved to dance, which is how she and my grandfather met. I grew up with stories of her feet hurting in her shoes, but she would continue to dance.

My grandfather’s writing looks almost like scribbles on a letter dated July 27, 1944, less than two months before that bullet struck him in the knee. It has an army examination stamp on it. But the letter’s greeting “Hello Darling” and the farewell of “Loving you always” are clear as day. Staring at the letter, I think about the specific moment my grandmother received it in the mail. Was it a sign of relief for my grandmother, knowing he was still alive?

They married on Aug. 31, 1946, after the war in Europe and the Pacific had both ended, but a year before my grandfather was honorably discharged from the Army. My grandmother was two months pregnant at the time with their firstborn, my aunt Connie. My grandfather prayed for all girls, and that is what he received—four girls—until my uncle and father were born. He always said he prayed for this because he did not want his boys to be drafted.

I carefully hold in my hands my grandfather’s honorable discharge paperwork. The sheet of paper is so delicate I unfold it with care. Stains, rips and faint words make it hard to read the historical document, but it is manageable as I trace the footsteps of my grandfather. He fought in the battle of Naples-Foggia, then Rome-Arno and another that’s illegible. It lists his medals: World War II Victory Medal. American Theater Ribbon. European, African, Middle Eastern Ribbon W/1 Bronze Star. Good Conduct Medal. And there, the last one: Purple Heart Medal. At the bottom of the document, it shows his thumbprint. I graze my hand over the print as I think of my grandpa. It was a seal of approval for his discharge on March 2, 1947.

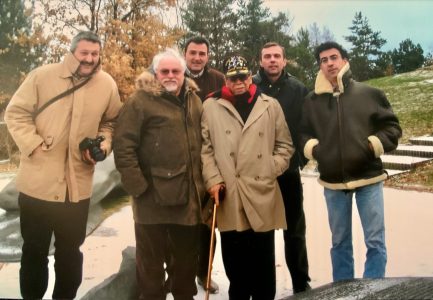

My grandfather always said the one thing he wanted to do before his passing was to go back to Italy. It was in 2007 that he got his wish. He was 87 years old. My aunt Norma accompanied him on a trip to Italy, where she says my grandfather was treated like royalty. When people knew my grandfather was coming, reporters and others gathered on the streets in a parade line. It was there my grandfather met Valerio and Renzo, the authors of the book about his division, and they took him to the World War II museum in Imola and Monte Battaglia where his division fought.

Valerio and Ranzo showed my grandfather the exact spot he got wounded, where he laid for hours in the rain, wondering if that was his last moment. My aunt tells me he froze in silence staring at that spot for 10 minutes. I can only imagine what my grandfather was thinking about as the memories came flooding back. There he was at 87 years old, seeing his life flash before his very eyes. What a life he has lived.

I started this search for my grandfather because of the fear I would one day forget my memories of him. But as I pieced together his life, I found more than just his story. I found myself.

My grandpa loved poetry. He loved listening to the band The Doors, because of Jim Morrison’s lyricism.

I sit here on the living room floor, listening to the sweet sound of Glen Miller on vinyl. I can’t help but feel so close to my grandpa at these moments. I pull from the box one of my grandfather’s favorite poems: “Soldier” by George L. Skypeck. One line in particular draws me in, “I have seen the face of terror; felt the stinging cold of fear; and enjoyed the sweet taste of moment’s love.” I think about what it means to me. My grandfather witnessed many deaths that were brutal in war. Many times he thought it would have been the end. However, through it and throughout his life he carried the love of the little things, “sweet moment’s love.” All these years, I see myself letting life go by quickly, and through it, I’ve lost who I am and the things that make me happy.

Writing has always been something that has come easy to me, whether it be storytelling or poetry. The family says I got it from him. He was a sweet man of few words, with a heart of gold. It has been a story I’ve been wanting to write for years, but I felt I couldn’t do it because I wouldn’t be able to bear the pain. I have never felt more like a writer than right now while writing his story.

It was here, searching and getting to know him, that I found a little piece of me, again. A girl who loves to write, read poetry, listen to big bands, draw, and, most of all, family.

Just like her grandpa.